The way you remember your story is important. Your family’s stories and their ways of telling them tell you about who you are. But there is so much missing.

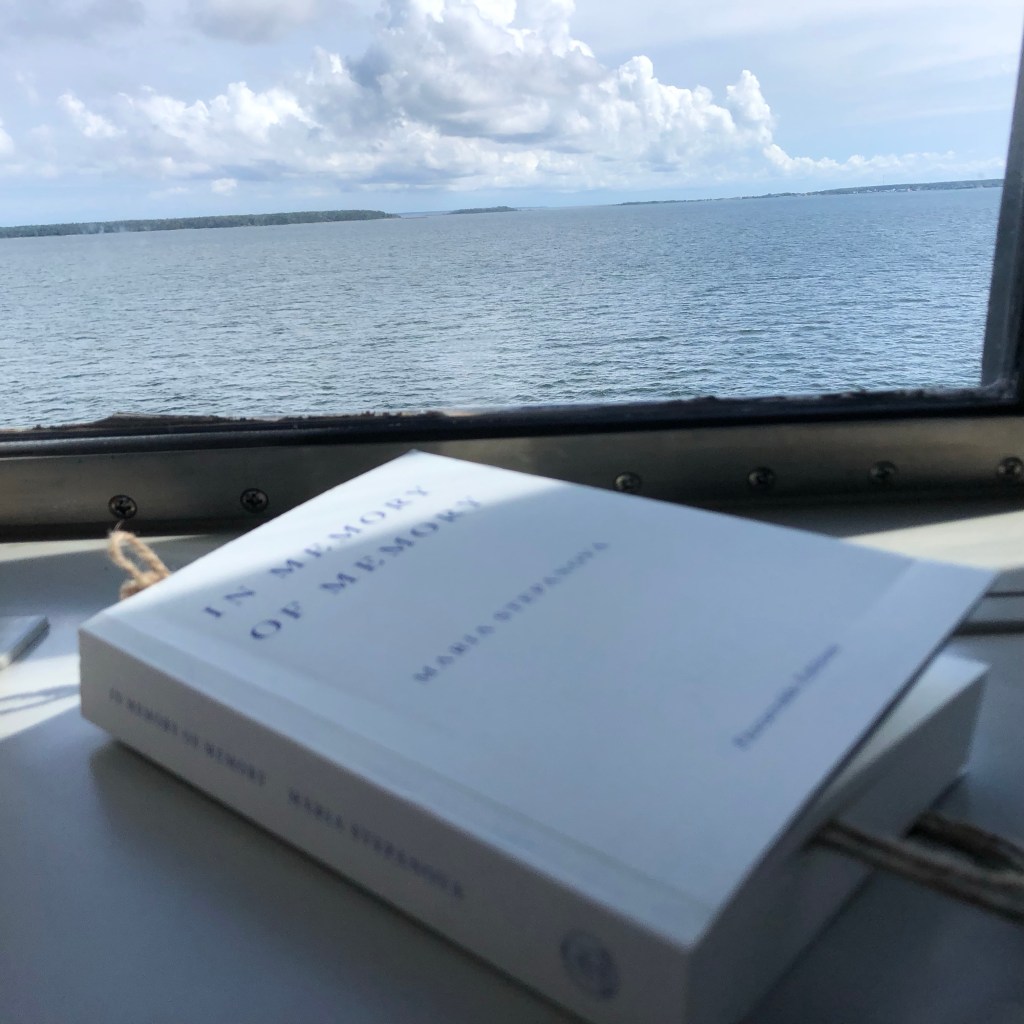

Maria Stepanova comes from a long line of Russian Jews, and none of her immediate family perished in the Gulag or the Shoah. That’s a story in itself. Stepanova published In Memory of Memory in 2017, and Sasha Dugdale’s translation came out in 2021. It took me another two years and a long summer holiday coach-ferry-train journey from Riga to central Finland to open it. But reading it as I crossed land and sea once ruled from Moscow and St Petersburg made sense. And then this took another couple of weeks to write.

What do I remember? Stepanova travelling hundreds of miles to see the house one of her ancestors lived in; only to travel hundreds of miles back, to learn her friend had told her the wrong building. Stepanova trying to enter a cemetery now overgrown with waist-high thistles; too soon realizing that finding a family grave in this thicket was both painful and hopeless. Stepanova’s parents moving to Germany in the 1990s, when travel was possible again; and her staying in Moscow, because so many things were possible again. Until they weren’t. Stepanova’s great grandmother on the barricades in revolutionary St Petersburg and in medical school in Paris. And Charlotte Salamon, painting for her life…

Fitzcarraldo Editions sent me this book with a white nonfiction cover, not a blue fiction one. But whenever we tell our stories, the line between history and her stories, or fact and fantasy, or truth and opinion, blurs. What “really” happened might not even be that important. How you feel about it, is.

Leave a comment