“So then they founded a women’s guard here, and anyhow I’m such an enthusiastic person so of course I went there first […] You can’t believe how enthusiastic I was about going to the front. Now I am going back on watch at eight although I just came off duty.” (Sally Rosendahl, one of the first Tampere volunteers, letter of 15 March 1918).

“The men proposed retreating, but the women said they had come to fight and they did not retreat. They pushed on with the attack, towards certain death. The butchers withdrew. The women soldiers bore the glory for many victories. When the men’s courage had failed already, the women persisted with the attack or held their positions.” (Lehtisaari (ed.), Punakaarti rintamaalla. Luokkasodan muistoa/The Red Guard on the Front: Memories of Class War, Leningrad 1929)

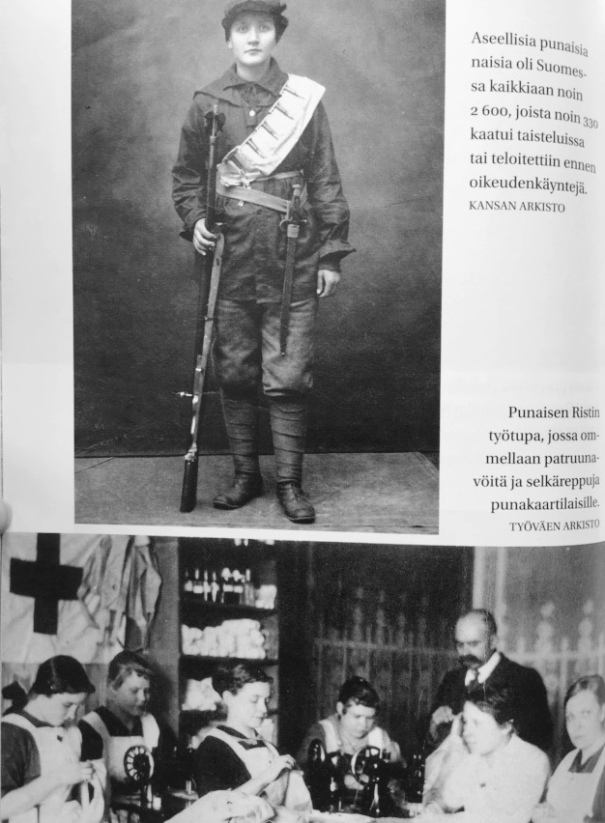

One of the 2600 women Red fighters in the Finnish civil war (Finnish National Archive) / Red Cross workers sewing rucksacks etc. for the Red Guard (Finnish Workers’ Archive)

These citations and images are just a few of the memories collected in Tiina Lintunen’s Punaisten naisten tiet/The Red Women’s Paths (my translations). The women were involved in all sorts of ways: cooking food, making coffee, sewing, as nurses, in telephone centres and messaging, as well as on the front itself. Lintunen researches the motivations and actions of these women in the Pori area in Western Finland, following up with court judgements and the long-term effects of being on the losing side in Finland’s civil war.

The immediate consequence was often months of waiting – if not dying – in near-starvation conditions in prison camps before their case went to court. The daughter of one woman, Katri, remembers the story of how her mother stole fresh bread from her own mother’s kitchen and was became hysterical when her little sister wanted to leave the house with red ribbons in her hair. Katri was sure that her sister would be arrested for openly supporting the Reds. Another woman remembers her teacher knocking a boy’s head against a brick wall for taking 1 May, the international workers’ day, off school.

Red widows were encouraged to put their children in homes for “care and re-education” – though few did – and had to wait until the 1940s to get war widow’s pensions on the same level as White widows. It took until 1973 before the remaining survivors received compensation for their time in prison camps.

Some women fled over the eastern border to the Soviet Union and rose to prominent positions until Stalin’s terror of the 1930s. Others ended up as some of the 40% of the US communist party members who were Finnish exiles in the 1920s. But the majority them went back home to work, in service, in textile factories, or on the land – nearly all of them were workers in the first place, after all.

What is striking is that in the years after the civil war, even though the Whites had won, many of the social reforms which the Reds wanted became law in the following decade. Smallholders got the right to own their land and school education became compulsory in 1918, and it became possible to officially withdraw membership of the Lutheran Church in 1922. Nevertheless, the history of it was written by the winners and it has taken a long time for the other side of the story to get official recognition.

Tiina Lintunen’s PhD research is publicly accessible, with an English summary, on the Turku University website. She also has a chapter on the Red women in the English-language study of the Finnish Civil War. This book is doing well and is also available as an e-book – is it time for an English translation?

[…] blog Found in Translation, Kate Sotejeff-Wilson, a translator based in Finland, has recently reviewed Tiina Lintunen’s Punaisten naisten tiet (Red Women’s […]

[…] this close together with the stories of the Red women in the civil war, my favourite minor character was Martta, the brother’s wife who encouraged […]

[…] women fought against Napoleon too, as Alexievich notes – and over the border – to the Finnish Red women. Yet it is not well known, as it was not even spoken about, let alone honoured, until Alexievich […]